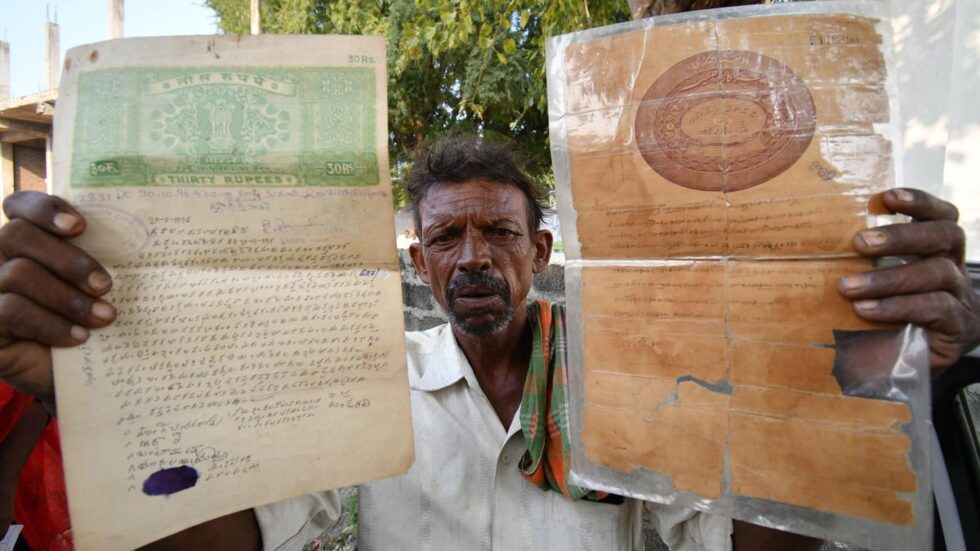

For decades, farmers across Telangana have cultivated land bought through Sada Bainamas – unregistered agreements common in the past – but remain denied legal ownership due to procedural hurdles.

Maruthaiah (70) of Bhojannapeta village near Peddapalli has been waiting for years to regularise 22 guntas of land his father bought in the early 1980s. Revenue officials insist on an affidavit from the legal heirs of the original seller – often deceased, untraceable or unwilling – leaving farmers trapped in limbo.

This affidavit requirement has become the biggest obstacle for thousands of small and marginal farmers, despite their names appearing in official “enjoyment columns” and decades of continuous cultivation. Rising land prices have further reduced cooperation from sellers’ heirs.

Farmer leader Kanneganti Ravi calls the rule illogical, arguing that possession, ground inspection and local enquiries should be sufficient proof. While officials claim progress in processing applications, farmers allege delays, corruption and selective enforcement.

The problem is worse in villages merged with municipal corporations, where regularisation is denied altogether and registration costs are prohibitive. As a result, land tilled for generations remains legally out of reachv – held hostage by affidavits, paperwork and an inflexible system.